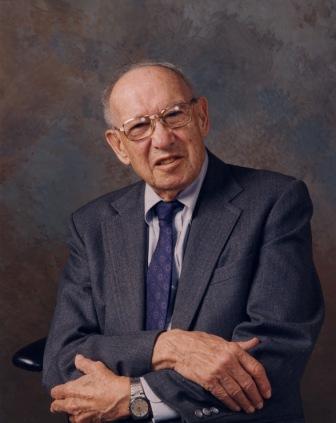

Steve Forbes, the president and CEO of Forbes and editor-in-Chief of Forbes Magazine in his tribute to Peter F Drucker called him 'the most influential management guru of the modern era'. Jerry Thomas explores the faith of the father of the modern management.

Steve Forbes, the president and CEO of Forbes and editor-in-Chief of Forbes Magazine in his tribute to Peter F Drucker called him 'the most influential management guru of the modern era'. Jerry Thomas explores the faith of the father of the modern management.

The New York Times once titled an article on Peter F Drucker as "The Man who Invented Management' (January 11, 1998). Steve Forbes, the president and CEO of Forbes and editor-in-Chief of Forbes Magazine in his tribute to Drucker called him 'the most influential management guru of the modern era' (The Wall Street Journal, November 15, 2005).

These descriptions are not an exaggeration for a man who first predicted, identified or codified the concepts like corporation, manager, knowledge worker, outsourcing etc., as we know today.

Drucker wrote 40 books and thousands of articles. He was also a much sought-after business consultant among the corporates. Documenting the influence of Drucker the Economist wrote, "He changed the course of thousands of businesses. He spawned two huge revolutions at General Electric-first when GE followed the radical decentralization he preached in the 1950s, and again in the 1980s when Jack Welch rebuilt the company around Mr Drucker's belief that it should be first or second in a line of business, or else get out ('Trusting the teacher in the grey-flannel suit' November 17, 2005). In short, one can say that Drucker was the sage of the capitalism.

However, there is an uncanny side to this sage of capitalism. Michael Lewis observed that in almost all of the writings of Drucker, there is a subtle scorn and a deep ambivalence towards capitalism (the New York Times, January 11, 1998). Whether one agrees with this or not, it is an indisputable fact that Drucker turned his interest to the nonprofit organization towards the end of his life. Drucker considered pastoral mega churches as the most important institution in America, and nonprofit organizations as the society of modern era.

In fact, for Drucker, business management was only a minor part of the discipline of management. In his book 'Management Challenges for the 21st Century', Drucker wrote that the very paradigm which considers management as a synonym of business management is historically wrong and needs to be replaced to face the challenges of the 21st Century. "The first practical application of management theory did not take place in a business but in nonprofits and government agencies", pointed out Drucker in this book. He further wrote, "the first job to which the term "Manager" in its present meaning was applied was not in business. It was the City Manager-an American invention of the early years of the century." Drucker added that "The first management congress-Prague in 1922-was not organized by business people but by Herbert Hoover, then the US Secretary of Commerce, and Thomas Masaryk, a world-famous historian and the founding President of the new Czechoslovak Republic".

Drucker argued that the identification of management with business management was a later development, a caricature that has now outlived its utility. The stress on nonprofit organizations rather than business houses, by the 'inventor' of management, is not difficult to grasp when one understands the spiritual roots of Drucker's management principles.

Spirituality of the 'Inventor' of Management

Drucker was born in 1909 in an Austrian upper middle-class family and educated in Vienna and Germany. He did his doctoral studies in international and public law from Frankfurt University in 1931. His record in academics and inclination should have made him a distinguished academician in any of the universities. But the totalitarian Nazism shook the young Drucker. He narrowly escaped the Nazi regime and adopted America as his nation. The oppression under Nazi regime made him think about the root causes of totalitarianism.

At that time he accidentally began to read the writings of the Christian philosopher Soren Kierkegaard and was deeply influenced by those. He even taught himself Danish to read the then untranslated works of Kierkegaard. Though Drucker was bought up in a nominal Christian family, the writings of Kierkegaard made him a firm believer. He continued to be a practicing Christian and often helped Churches like Christian evangelical Saddleback Community Church in Califorina, where Pastor Rick Warren heads, with his gift- the management advices. Drucker considered his article on Kierkegaard as the best piece he ever wrote and in that one can see the 'creed' of Drucker's faith.

According to Drucker, while philosophers like Hegel, Rousseau and Marx asked the question: How is society possible? Kierkegaard liked all orthodox Christian philosophers asked the question: How is human existence possible? Drucker, for whom asking the right questions was very important, considered that these questions were of unique significance. He argued, &

quot;For if you start with the question, How is society possible?, without asking at the same time, How is human existence possible?, you arrive inevitably at a negative concept of individual existence and freedom: individual freedom is then what does not disturb society. Thus freedom becomes something that has no function and no autonomous existence of its own." Drucker continued "to define freedom as that which has no function is, however, to deny the existence of freedom. For nothing survives in society save it have a function". He then critiqued the contemporaries of Kierkegaard for they laid emphasis on equality at the cost of freedom. This false value, Drucker concluded, was the root of the 19th totalitarianism .

Here, Drucker found Kierkegaard's answer, illuminating and liberating. Kierkegaard pointed out that human beings have a paradoxical existence; one in the fleeting moments of time and the other in the permanent realm of eternity. Here in this life in time, man has relationships and failures and success. From the perspective of time, man is temporary and institutions are permanent. The question how is society possible? seems more relevant from this perspective. But the view of eternity comes in direct conflict with the perspective of time. In eternity, man stands alone in the sight of God.

Moreover, Drucker writes, "In eternity, however, in the realm of the spirit, 'in the sight of God,' to use one of Kierkegaard's favorite terms, it is society which does not exist. In eternity only the individual does exist." However, such life even if ethically upright, leads to despair; a life that is negated between the life in time and the life in eternity. Kierkegaard suggests that there is a biblical way to overcome this despair; live by faith in the Biblical God. Drucker unambiguously and boldly summarized his view, "In faith the individual becomes the universal, ceases to be isolated, becomes meaningful and absolute; hence in faith there is a true ethic. And in faith existence in society becomes meaningful, too, as existence in true charity.

The faith is not what today is so often glibly called a 'mystical experience'-something that can apparently be induced by the proper breathing exercises or by prolonged exposure to Bach." Drucker cautioned that this faith is not irrational, sentimental, emotional, or spontaneous but "comes as the result of serious thinking and learning, of rigid discipline, of complete sobriety, of humbleness, and of the self's subordination to a higher, an absolute will".

Spiritual Applications in Management

From these spiritual insights, Drucker applied two principles that guided all his management writings; the permanence of an individual and a community that lives by faith. The Wall Street Journal aptly captured the essence of Drucker's principles when it said "Peter Drucker's legacy includes simple advice: It's all about people" ( November 14, 2005). This was not just a management theory for Drucker but his very life. He believed in 'meeting people'. Throughout his life, he never appointed a secretary to attend his phone calls, he did it himself. He kept in contact with all his students and even knew the names of their spouses.

Drucker also bought a communitarian perspective to management. Ken Witty, who made a documentary titled 'Peter Drucker: An Intellectual Journey', said, "He brings a communitarian philosophy to his consulting. That was something I really never heard about until Peter emphasized it in our interviews. He said that what he is all about is this search for community, the search for where people and organizations find community for noneconomic reasons." ('Peter Drucker's Search for Community', BusinessWeek, December 24, 2002.).

No wonder then that Drucker was associated with nonprofits and pastoral mega Churches often giving them his piece of advices pro bono. Capitalism, for Drucker, was never about products and profits, it was all about people and values; and management was doing the right things for the people. There was always a spiritual dimension to whatever Drucker taught. In the final analysis, is he not the one who said, "Management deals with the nature of God, the nature of man and the nature of devil" ('Reviving Moral Sciences', Claremont Institute).

{moscomment}