Writer: The Don

After 10th Century AD, Buddhist Scholar Panini is falsely shown as a Brahmin … much after his death. How was this false narrative created? Who Authored Astadhyayi (Sanskrit Grammar)?

Current Understanding of Panini:

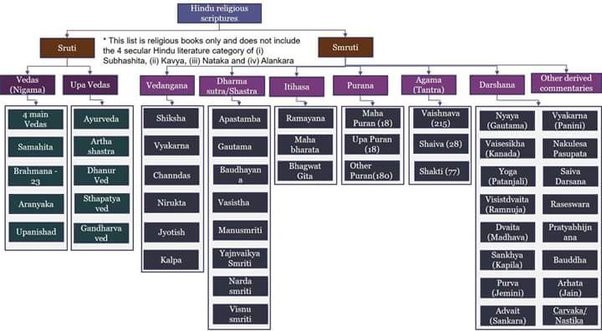

In general, our current understanding of Panini revolves around his identity as a Brahmin Scholar and the Creator of Sanskrit. He is renowned as the Father of Linguistics. His notable work, the “ASHTADHYAYI,” is a Sanskrit treatise composed during the 6th to 5th century BCE (though exact dates remain speculative) that holds a significant place in linguistic history. This comprehensive work, consisting of 4000 sutras, outlines the principles of phonetics and grammar that had developed within the context of the Vedic religion.

Panini meticulously organized the “ASHTADHYAYI” into eight chapters, further subdivided into quarter chapters. This influential work established the linguistic norms for Classical Sanskrit. It’s worth noting that the foundation of many Indian languages has roots in Sanskrit, and Panini’s role in crafting this language was instrumental. His efforts contributed to the dissemination of Sanskrit throughout the various subcontinents of India.

Panini’s grammatical framework is acknowledged as one of the world’s earliest formal languages. His contributions encompass the unveiling of the Vyakarana and Shiksha systems. In his work, Panini employed terminology that also appeared in texts preceding the Aranyakas, Brahmin literature, Upanishads, and Vedic codes.

While comprehensive biographical records or written accounts about Panini are scarce, it is believed that he was born around the 4th, 5th, or 6th century BCE. Estimations regarding his birth date vary, and there’s uncertainty surrounding his birthplace, which is said to be Shalatula near the Indus River, now located in present-day Pakistan. These details, however, rest on conjecture rather than concrete evidence. Similarly, there is limited substantiation regarding the extent of his scholarly endeavors.

In the book “Religion and Society of the Panini Age” by Gajanan Pandey – “पाणिनि कालीन धर्म एवं समाज” (available in Hindi, with the first edition published in 2005), comprehensive insights into Panini’s familial background, birthplace, mentors, and his acquisition of grammatical knowledge are presented. The book reveals that Panini’s parents were Pani and Dakshi. Furthermore, it identifies Varsha as Panini’s esteemed teacher and mentor. This valuable source expounds upon these aspects, offering a deeper understanding of Panini’s life and the socio-religious milieu during his era.

Pingala, Panini’s sibling, and Kautsa, hold the position of Panini’s principal disciple. According to Gajanan Pandey, Panini’s grammatical knowledge was attained through the divine blessings of Shankar (Shiva). Katyayan, a contemporary of Panini, both engaged with and opposed his teachings. An intriguing narrative unfolds, recounting how Aindra-Vyākaraṇa suffered destruction due to the divine ire of Shiva upon Katyayan, who had bested Panini in a contest. In response, Katyayan embarked on a period of devout penance, eventually appeasing Shiva, who then bestowed upon Katyayan the profound knowledge of Panini’s grammar. This tale reflects the intricate interplay of divine favour, rivalry, and eventual enlightenment.

In Gajanan Pandey’s account, it is mentioned that the Astadhyayi comprises a total of 4000 sutras. Additionally, based on the Swar Siddhanth Chandrika, he notes an alternate perspective suggesting that the Astadhyayi consists of 3995 sutras.

Is the Current Understanding Correct? Evidence Against the Current Understanding:

This is the extent of our current knowledge regarding Panini and his grammar treatise. I now pose a question to all of you: Is the information we possess about Panini accurate, or have we been intentionally led astray by a certain faction distorting the truth?

If you find yourself uncertain or unaware of the answer, allow me to elucidate that we have indeed been purposefully misled by a particular group, diverting us from the factual narrative.

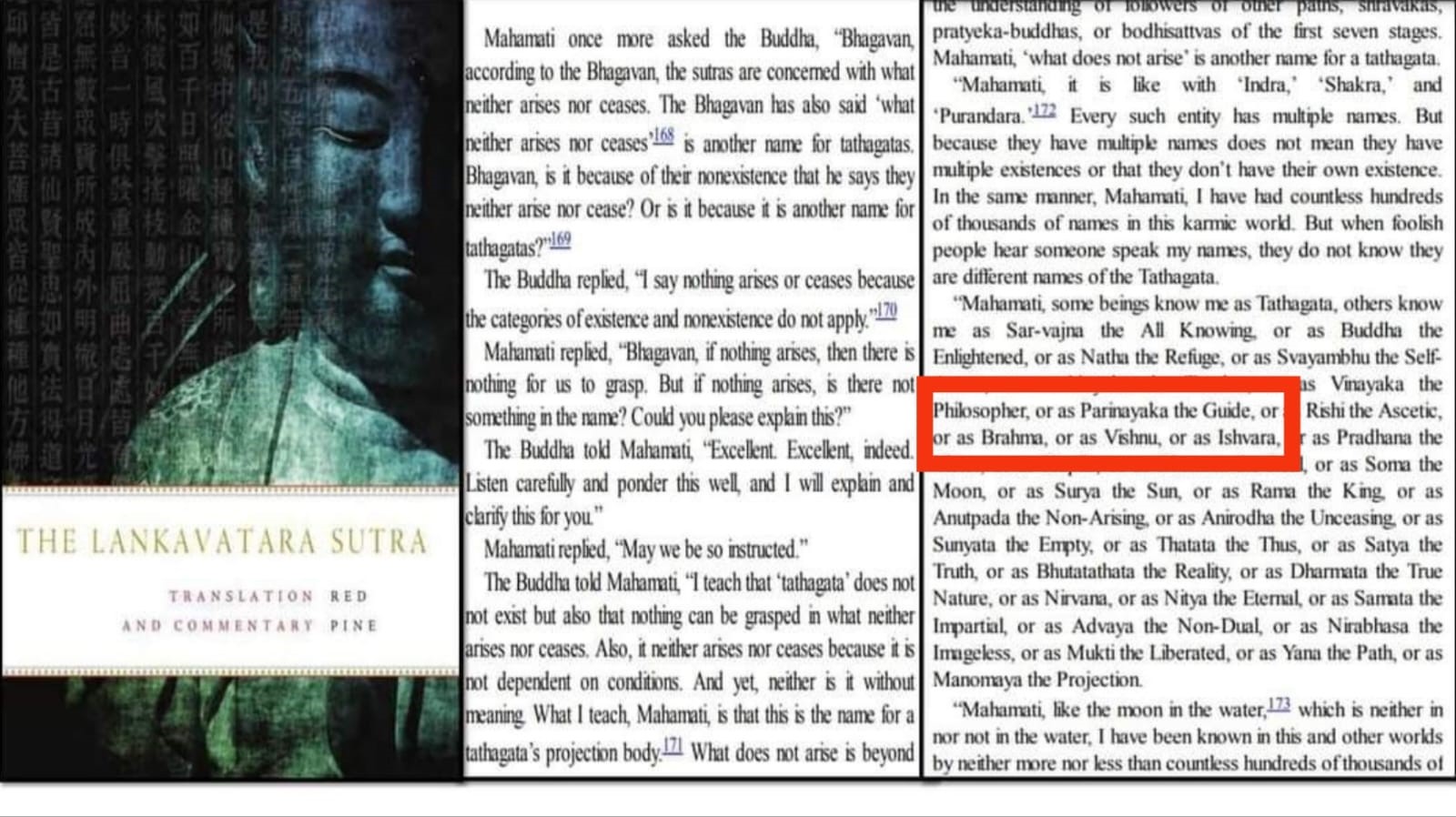

Contrary to the prevailing notion, Panini was not, in fact, a Brahmin Scholar; rather, he held the identity of a Buddhist Scholar. Furthermore, the blessings attributed to the Hindu deity Shiva were not bestowed upon Panini. Instead, it was Mahadeva who granted his blessings—an entity also recognized as Buddha; Mahadeva is one of Buddha’s names.I know this has shocked you!!! But there is enough evidence which I will cover in my followup articles. Just to give you a glimpse

Moreover, the grammar treatise authored by Panini was not intended for the Sanskrit language as commonly believed. It was, in reality, a grammar treatise for a mixed language known as Pali-Prakrit, sometimes referred to as hybrid Sanskrit. Contrary to the popular notion of a 4000-sutra composition, Panini’s work consisted of around 1000 sutras in the context of this Pali-Prakrit mixed language.

It’s important to acknowledge that Panini’s grammar treatise wasn’t the inaugural endeavour of its kind. Preceding Panini, other grammar treatises existed, with the earliest being Aindra-Vyākaraṇa, which wasn’t in the Sanskrit language.

Additionally, the designation “Astadhyayi” for Panini’s grammar treatise did not emerge until the 12th century AD.

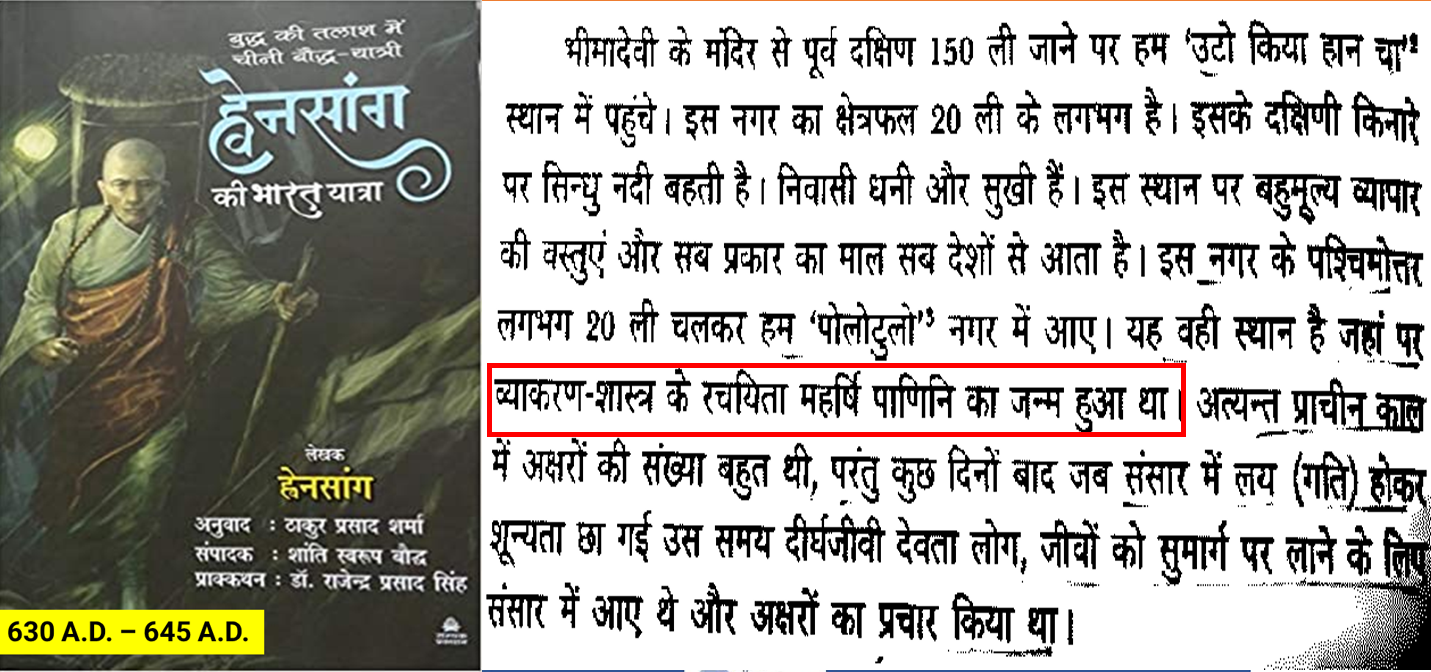

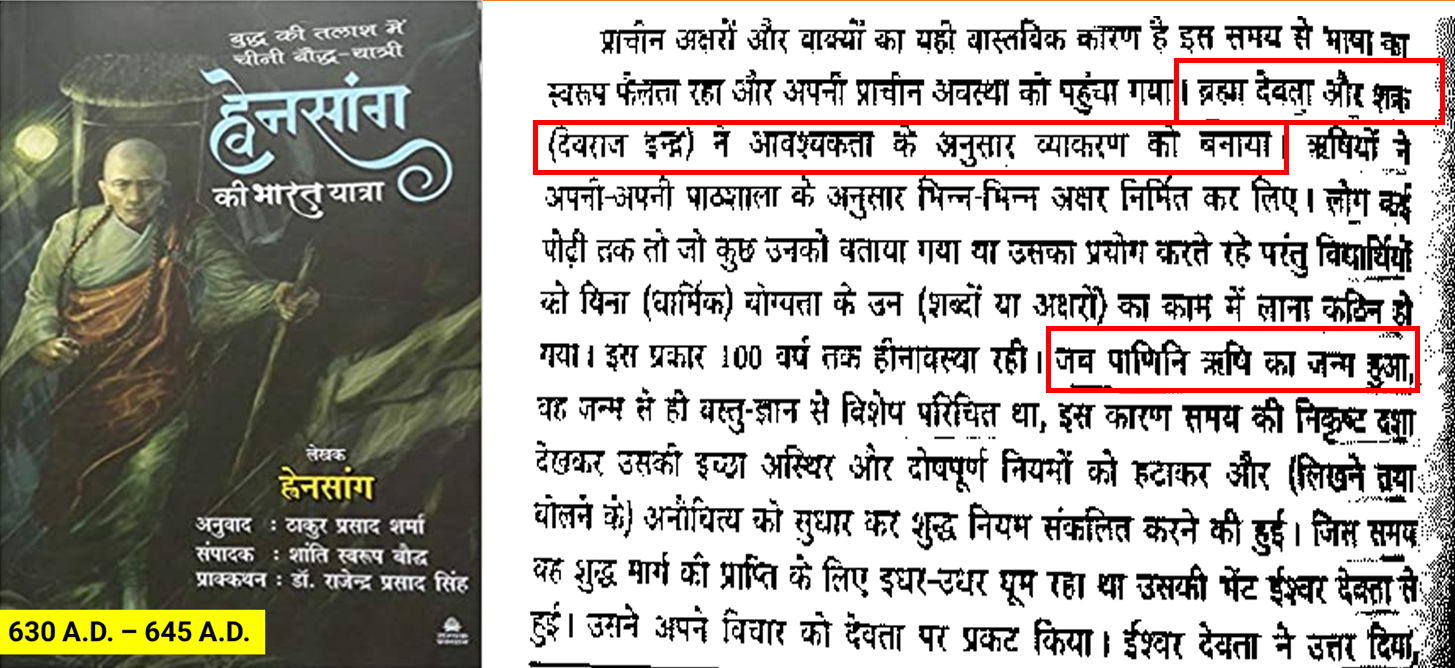

You might naturally seek evidence substantiating these claims. Let me commence by providing evidence from the travel notes of the Chinese Buddhist pilgrim Hiuen-Tsang. According to Hiuen-Tsang, Panini’s birthplace was the village of Śālātura, situated in the city of Attock, within the region of Gandhara, now located in present-day Pakistan.

Prior to the composition of Panini’s grammar treatise, the landscape included the presence of Brahma Devata and Aindra Vyakarana. However, these resources were of limited utility for students. Faced with this predicament, Panini embarked on a quest for the correct path, leading him to encounter Ishwar Devata, who would illuminate his journey.

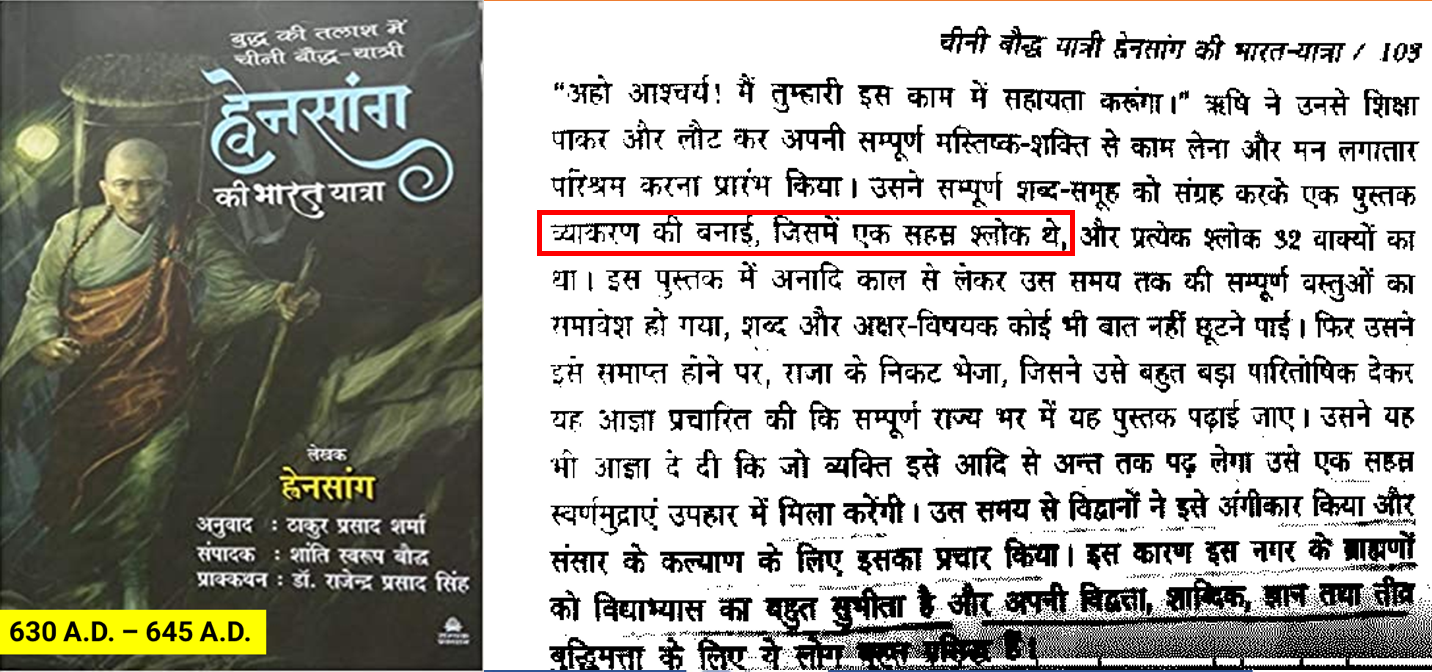

Guided by Ishwar Devata, Panini acquired the knowledge necessary to craft his grammar treatise, which ultimately encompassed a mere 1000 Sutras. As we progress, we will unveil the identity of this Ishwar Devata. However, for the present moment, it’s crucial to note that this Ishwar Devata is distinct from the deity Shiva, as Gajanan Pandey erroneously asserts in his book.

Based on the travel notes of Hiuen-Tsang, who journeyed to India during the 7th Century AD, three pivotal insights into Panini’s life emerge:

Firstly, the birthplace of Panini is identified as Śālātura, located in the city of Attock within the region of Gandhara—now situated in present-day Pakistan.

Secondly, it is revealed that prior to Panini’s creation of his grammar treatise, Brahma Devata and Aindra Vyakarana were already established and employed by students. However, these resources proved to be of limited assistance, indicating that Panini’s grammar treatise was not the inaugural endeavour in this domain, despite the assertions made by certain groups.

Thirdly, Panini sought guidance and knowledge from Ishwar Devata when he was on a quest for the right path. This crucially implies that Panini’s alignment was not exclusively with the Vedic religion. Subsequently, guided by Ishwar Devata, he authored a grammar treatise comprising only 1000 Sutras. This stands in stark contrast to the modern understanding of the Astadhyayi Sanskrit grammar treatise, which contains 4000 Sutras.

Remarkably, during Hiuen-Tsang’s visit to India in the 7th Century AD, the Astadhyayi Sanskrit Grammar was not yet in existence.

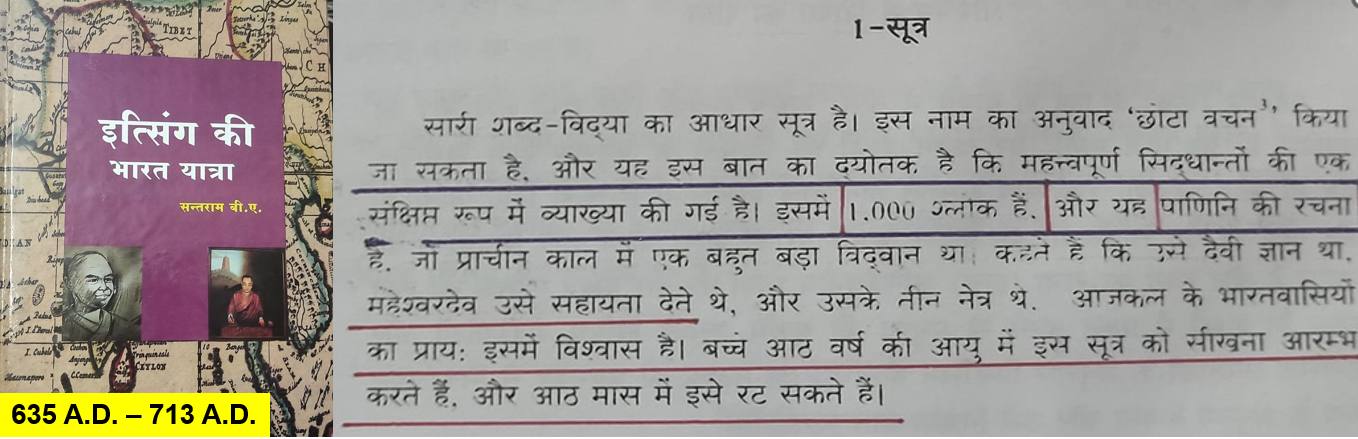

Now, let’s turn to I-tsing, a Chinese Buddhist pilgrim from the 7th century who meticulously documented his travels to India. I-tsing also corroborates the narrative, noting that Panini composed a Vyakarana of 1000 Sutras with the assistance of Maheshwar Dev, a three-eyed entity. This reinforces the distinct perspective on Panini’s life and achievements.

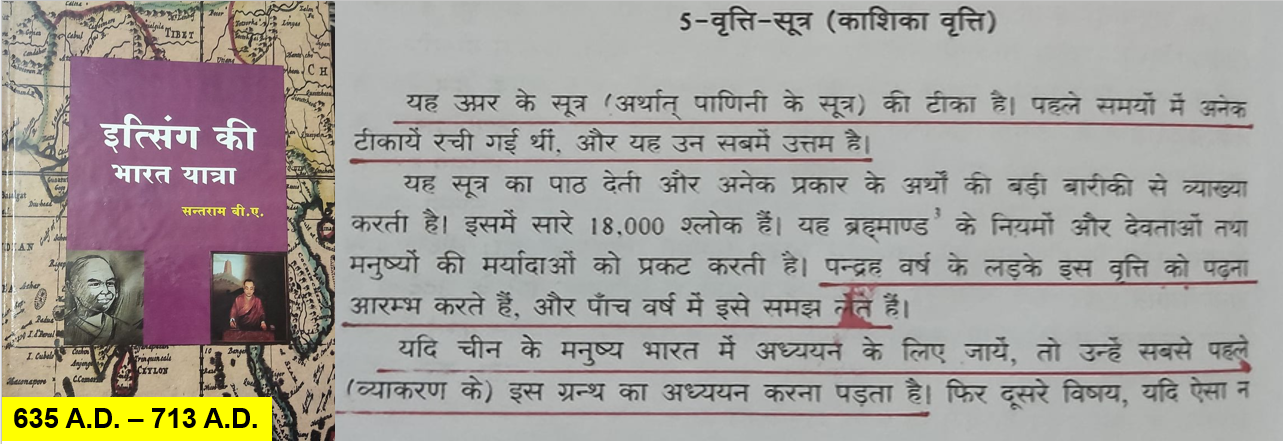

I-tsing’s records include information about the Kashika Vritti Sutra, comprising 18,000 shlokas. This work serves as a commentary or tika on Panini’s grammar treatise. Interestingly, students arriving from China were initially required to study the Kashika Vritti Sutra as a foundational step before delving into other subjects.

The Kashika Vritti Sutra, authored by Jayāditya, a proponent of the Triratna belief encompassing the Buddha, the Dhamma, and the Sangha, takes centre stage. Notably, Jayāditya’s passing occurred three decades prior to I-tsing’s documentation, placing his demise within the years 661 AD to 662 AD.

I-tsing also discusses a Commentary/Tika called Churni, comprising 24,000 Shlokas. This Commentary/Tika interprets the Kashika vritti Sutra, which, in turn, is an interpretation of Panini’s grammar treatise authored by Patanjali. In the footnotes, it is evident that Patanjali’s work alludes to his Mahabashya, consisting of only three chapters (The Mahabashya that we are familiar with today, bearing Patanjali’s name, encompasses 85 chapters).

I-tsing mentions that following Churni, there is a Commentary/Tika of Churni known as the Bhartruhari Shastra Commentary/Tika, consisting of 25,000 Shlokas and authored by Bhartruhari.

From It-sing’s Travel Notes, which document his visit to India in the 7th century AD, we glean four significant insights regarding Panini:

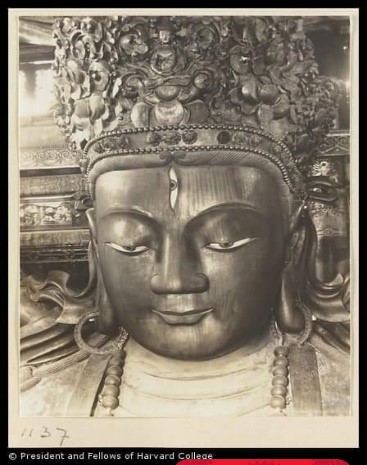

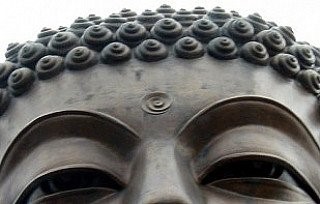

Firstly, Panini crafted 1000 Vyakarana Sutras with the assistance of Maheshwar Dev, who is described as having three eyes, symbolizing Buddha rather than the deity Shiva. The concept of the third eye in Buddha statues represents an abstract idea denoting an invisible eye that grants perception of a reality beyond ordinary human sight. It serves as a metaphorical gateway to the deeper realms of true inner consciousness.

Secondly, in the 7th century AD, Jayāditya, a proponent of Triratna (the Buddha, the Dhamma, and the Sangha), composed the Kashika Vritti Sutra, a commentary of Panini’s grammar treatise, consisting of 18,000 Shlokas.

Thirdly, Patanjali authored the Churni Commentary/Tika, spanning 24,000 Shlokas. This Commentary/Tika interprets the Kashika Vritti Sutra, which, in turn, interprets Panini’s grammar treatise. This information helps establish the time period of Patanjali. Since Patanjali wrote a commentary for Jayāditya’s Kashika Vritti Sutra, and Jayāditya lived in the 7th century AD, it suggests that Patanjali likely lived during or after that period, contradicting the notion that he lived in the 2nd century BC. Additionally, if this Churni Commentary is the same as the Mahabashya, as some believe, it implies that Patanjali did not compose commentaries on Pāṇini’s Astadhyayi or Kātyāyana’s Vārttika-sūtra.

Fourthly, Bhartruhari authored the Bhartruhari Shastra, a Commentary/Tika of the Churni Commentary/Tika, spanning 25,000 Shlokas.

During I-tsing’s visit to India in the 7th century AD, Panini’s Astadhyayi Sanskrit Grammar was not available.

Additionally, evidence from Al-Beruni, who visited India in the 11th century AD, can be found in his work “Al-Beruni’s India Vol. 1 Chapter 13.” In this text, he lists grammar books available in India by the 11th century AD in chronological order. Panini’s Vyakarana is mentioned in fourth place, preceded by Aindra Vyakarana, Candra Vyakarana composed by the Buddhist monk Candra, and Sakata Vyakarana. This suggests that Panini’s work was still present and recognized, even in the 11th century AD.

It’s worth noting that these insights challenge traditional beliefs about the dating of Panini and his works, shedding new light on the historical context of Indian grammar and philosophy.

During that era, Shah Anandapala, both a ruler and a student of Ugrabhūti, issued a decree to distribute 200,000 dirhams among those who diligently studied his master Ugrabhūti’s book. As a consequence, scholars of that period ceased copying other grammatical texts and instead actively promoted Śiṣyahitā Vṛtti, elevating it to widespread popularity and great esteem.

In Al-Beruni’s India, Volume 1, Chapter 13, Al-Beruni records a narrative he was told about the genesis of grammar. According to this tale, Panini collaborated with Mahadeva to craft the grammar rules for King Samalvahana, who is understood to be the classical equivalent of the Satavahana ruler.

From Al-Beruni’s Travel Notes during his 11th Century AD visit to India, three key insights regarding Panini and grammar emerge:

Firstly, **Predecessors to Panini:** Before Panini’s grammar treatise, there were existing grammatical works, such as Aindra (Indra) Vyakarana, Candra Vyakarana, and Sakata Vyakarana. Notably, all of these were authored by Buddhist monks. It is important to note that these references to Indra and Brahma are not from the mythological stories of Brahmins but rather Buddhist figures associated with Buddha (I know you are shocked to read this, will be covering these in much detail in my followup articles).

Secondly, **Popularity of Śiṣyahitā Vṛtti Vyakarana:** In the 11th Century AD, Ugrabhūti’s Śiṣyahitā Vṛtti Vyakarana gained prominence, leading to the cessation of copying other grammatical texts. This work became highly regarded during this period.

Thirdly, **Origin Story of Panini’s Grammar:** Al-Beruni recounts a story about the origin of grammar, suggesting that Panini, with the assistance of Mahadeva, crafted the grammar for a ruler named King Samalvahana, who is understood to be analogous to the Satavahana dynasty. This narrative implies that Panini’s work may have been composed around the 1st or 2nd Century BC.

In conclusion:

– Panini’s birthplace is indicated as Śālātura, located in the city of Attock, in the region of Gandhara, which is now part of present-day Pakistan.

– Prior to Panini’s grammar treatise, other grammatical works existed, showing that Panini’s work was not the first.

– The story recounted by Al-Beruni suggests that Panini’s collaboration with Mahadeva in creating grammar may date to around the 1st or 2nd Century BC.

– Notably, there is no evidence of the 4,000 Sutra version of Panini’s Astadhyayi Sanskrit Grammar before the 11th Century AD.

– The use of Devanagari Lipi for Sanskrit, which developed fully by the 10th Century AD, implies that much of Hindu religious scripture, including the Astadhyayi Sanskrit Grammar, was likely composed after the 10th Century AD.

These insights challenge traditional dating and understanding of Panini and his works, suggesting a more complex and evolving history of grammar and linguistic traditions in ancient India.